At one time, replacement parts for the eyes must have seemed unimaginable. Nowadays, if the inner lens of the eye becomes clouded by a cataract, a routine surgery to swap it out with a new artificial lens restores vision.

But what happens if the outer lens of the eye (the cornea) becomes damaged or diseased? You can have that replaced, too. “It’s not as common as cataract surgery, but many people get corneal diseases after age 50 and may need a corneal transplant,” says Dr. Nandini Venkateswaran, a corneal and cataract surgeon at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

More than 49,000 corneal transplants occurred in 2021 in the US, according to the Eye Bank Association of America.

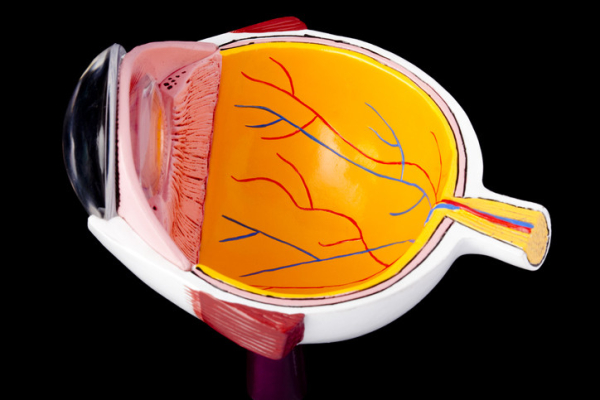

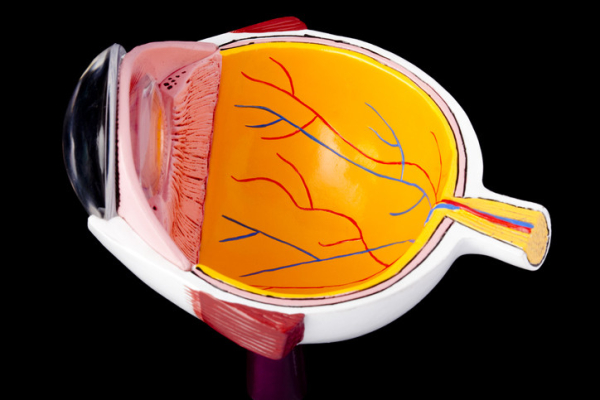

What is the cornea?

The cornea is a dome of clear tissue at the front of each eye, covering the iris and pupil, that acts as a windshield that protects the delicate eye apparatus behind it, and focuses light onto the retina, which sends signals that the brain turns into images (your vision).

You need this combo of windshield and camera lens to focus and see clearly. But many things can go wrong within the five layers of tissue that make up the cornea. That can make it hard to see and rob you of the ability to read, drive, work, and get through other activities in your day.

How does damage to the cornea occur?

It may stem from a number of causes:

- Injuries, such as a fall. “Falls are a big reason for people to come in with acute eye trauma. The cornea can be damaged easily if something pokes it,” Dr. Venkateswaran says.

- Previous eye surgeries. “Especially for adults who’ve had several eye surgeries — such as cataract and glaucoma surgeries — the inner layers of the cornea can become damaged and weakened with age,” she adds.

- Illness. Problems like severe corneal infections, or genetic conditions such as Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, can cause vision loss.

What are the options for treating corneal damage?

Cornea treatment depends on the type of problem you have and the extent of the damage. “It’s a stepwise approach. Sometimes wearing a specialty contact lens or using medications can decrease swelling or scarring in the cornea,” Dr. Venkateswaran says.

When damage can’t be repaired, surgeons can replace one or a few layers of the cornea (a partial-thickness transplant), or the whole thing (a full-thickness transplant).

The vast majority of transplants come from donor corneas that are obtained and processed by eye banks throughout the US. In some instances, such as when repeated transplants fail, an artificial cornea is an option. Recovery after corneal surgery can take up to a year.

How long-lasting are corneal transplants?

There’s always a risk that your body will reject a corneal transplant. It happens about a third of the time for full-thickness transplants. It occurs less often for partial-thickness transplants. Preventing rejection requires a lifetime of eye drops.

Still, transplant longevity varies. “I’ve seen transplants from 50 or 60 years ago and now they’re starting to show wear and tear. Other patients, for a variety of reasons — immune system attacks, intolerance to eye drops, or underlying conditions — may only have a transplant for five to 10 years before they need another,” Dr. Venkateswaran explains.

Preventive eye care can help preserve the cornea

It’s crucial to get regular comprehensive eye exams to make sure your corneas and the rest of your eyes are healthy.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends a comprehensive (dilated) eye exam

- at age 40

- every two to four years for people ages 40 to 54

- every one to three years for people ages 55 to 64

- every one to two years for people ages 65 and older.

You’ll need an eye exam more often if you have underlying conditions that increase your risk for eye disease, such as diabetes or a family history of corneal disease.

If you have any vision problems, such as eye pain, redness, blurred vision despite new glasses, or failing eyesight, see an eye doctor.

Fortunately, for people who do experience corneal damage, advances in surgical options are encouraging.

“Corneal transplants are a miracle,” Dr. Venkateswaran says. “I have patients whose quality of life was significantly decreased because they couldn’t see through their cloudy windshield. We can give them sight again, and we have the technology and medications to keep the transplant alive.”

About the Author

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

Heidi Godman is the executive editor of the Harvard Health Letter. Before coming to the Health Letter, she was an award-winning television news anchor and medical reporter for 25 years. Heidi was named a journalism fellow … See Full Bio View all posts by Heidi Godman