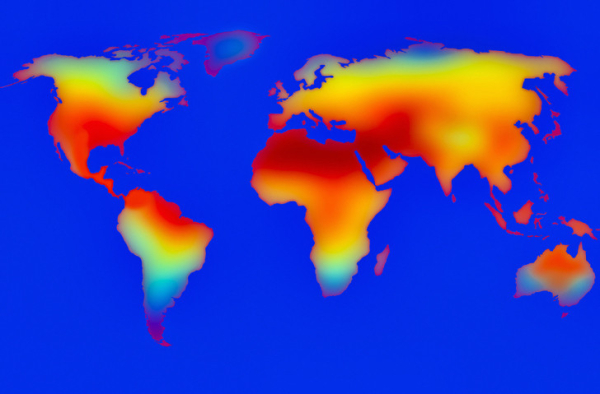

This spring, many parts of United States experienced historic heat waves. Now summer is officially underway, and experts are predicting hotter than normal temperatures across most of the country.

Extreme temperatures increase health risks for people with chronic conditions, including heart problems. If you do have a heart condition, here’s how to keep cool and protect yourself when temperatures rise.

How does hot weather affect the heart?

Not only does exposure to high heat increase the risk for heat exhaustion and heat stroke, but it can also place a particular burden on heart health. It stresses the cardiovascular system and makes the heart work harder. This can increase the chance of heart attacks, heart arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat), and heart failure.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the interaction of high heat and cardiovascular disease contributes to about a quarter of heat-related deaths.

And the higher the temperature, the greater the threat. A recent study in the journal Circulation looked at cardiovascular death rates over seven years in Kuwait, where daytime temperatures can reach triple digits in the hottest months. The researchers found a link between rising temperatures and the risk of cardiovascular deaths, with most occurring between temperatures of 95° F to 109° F.

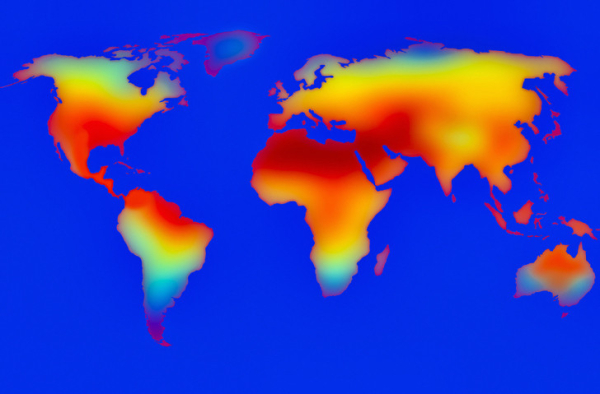

“Climate change is giving us more, and unprecedented, heat that can be deadly, especially for people with heart disease,” says Dr. Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

How does the body shed heat?

Your body is designed to shed extra heat in two major ways, each of which may affect the heart:

Radiation. When the air around you is cooler than your body, you radiate extra heat into the air. This process requires rerouting blood flow so that more of it goes to the skin.

Evaporation. Evaporating sweat helps cool you down by pulling heat away from your skin. When the air is dry, this works well. But when it’s hot and humid, sweat just sits on the skin as your body temperature rises.

When air temperature approaches or exceeds body temperature, especially in high humidity, the heart has to beat faster and pump harder to help your body shed heat. On a hot and humid day, your heart may circulate two to four times as much blood each minute compared with a cool day.

Some medicines meant to help the heart can add to problems on hot days. For example, beta blockers slow the heartbeat and hinder the heart’s ability to circulate blood fast enough for effective heat exchange. Diuretics (water pills) increase urine output and raise the risk of dehydration.

How can you protect yourself and your heart when temperatures rise?

While exposure to high heat and heat waves affects everyone, having existing heart problems raises your risk for heat-related illness and hospitalization. So it’s especially important to try to follow basic strategies for staying cool, including these:

- Monitor weather forecasts for heat advisories and stay inside on those days. If home is too hot, check with your town or city health department for cooling centers and other options to help you stay cool. If you venture outside, evening and early morning are often the coolest times. Rest in the shade whenever possible.

- When outside, try to drink 8 ounces of water every 20 minutes. Set a timer to remind you. “Never wait until you’re thirsty to drink,” says Dr. Bernstein. If you have heart failure, ask your doctor how much fluid you should drink daily, since fluids can build up and cause swelling. If you take diuretics, ask how much you should drink during hot weather.

- Avoid soda or fruit juice and limit alcohol. Soda and fruit juice may slow the passage of water from the digestive system to the bloodstream. While research is limited, some studies have found that excessive alcohol intake may raise risk for heat stroke during scorching weather.

- Protect your skin. Sunburn affects your body’s ability to cool down and increases dehydration. Wear a wide-brimmed hat, wraparound sunglasses, and lightweight, light-colored, loose-fitting clothing. Also, apply plenty of broad-spectrum or UVA/UVB protection sunscreen with SPF 30 or higher to all exposed skin 30 minutes before going out. Reapply every hour.

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

Matthew Solan is the executive editor of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. He previously served as executive editor for UCLA Health’s Healthy Years and as a contributor to Duke Medicine’s Health News and Weill Cornell Medical College’s … See Full Bio View all posts by Matthew Solan